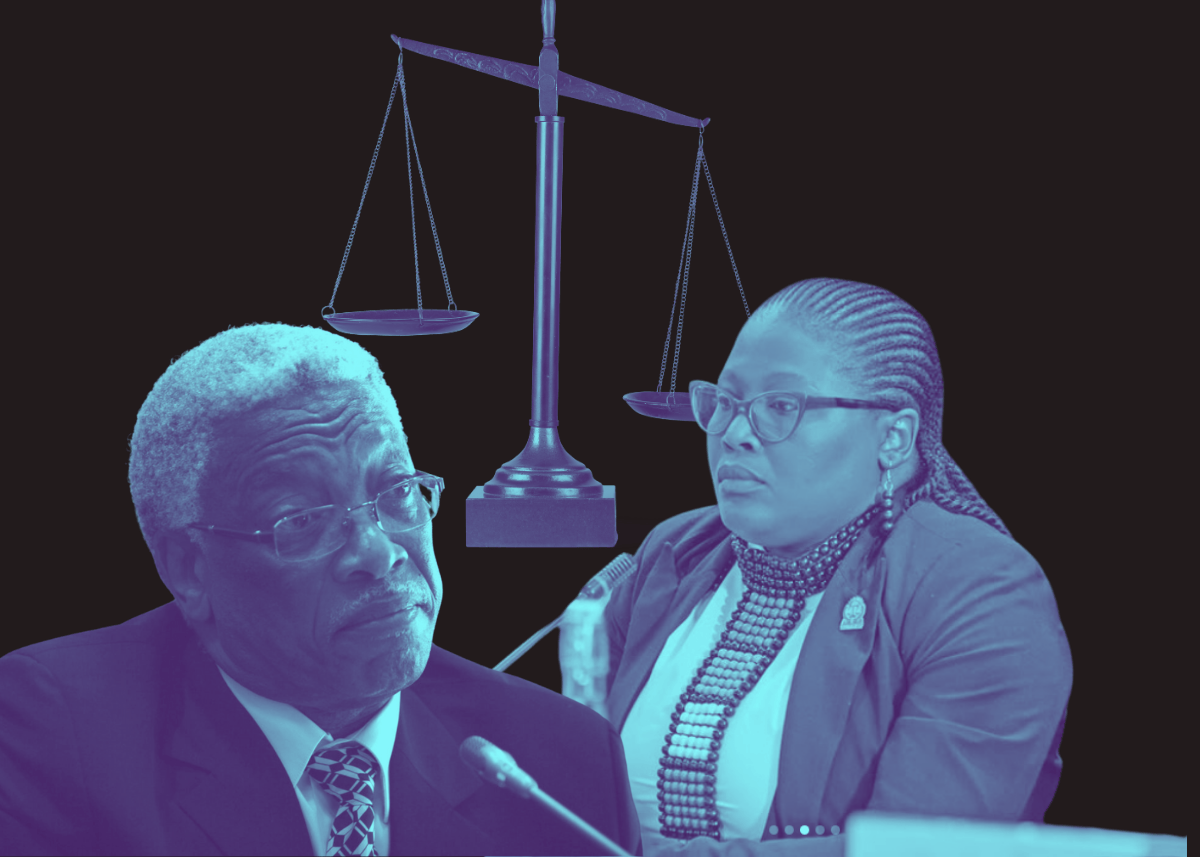

The sexual harassment inquiry into Eastern Cape Judge President Selby Mbenenge has shocked South Africa’s legal and judicial circles as well as the public at large.

Mbenenge is accused of sending suggestive videos, images, and text messages to a complainant over an extended period.�

These actions allegedly occurred in the context of a professional relationship, highlighting the power imbalance that lies at the heart of this case.

Power Imbalance and Consent: A Disturbing Reality

What complicates the allegations is the conduct of the complainant, who occasionally appeared to reciprocate Mbenenge’s advances. In certain instances, she engaged in flirtatious exchanges with the Judge President, raising questions about the nature of their relationship.�

Yet, we must consider that many victims of harassment, particularly in cases where there is an abuse of power, may not immediately resist suggestive conduct. Fear of reprisal, or uncertainty about how to react, can lead to passive or seemingly consenting participation.

The Psychology of Power Abuse in the Workplace

This case highlights an uncomfortable truth—victims of harassment, especially when faced with someone in a position of authority, may not immediately dismiss inappropriate conduct.�

When individuals fear victimisation or reprisal, or feel trapped in a dominant power structure, they may inadvertently act in a way that appears consensual or participative.�

However, these actions should not immediately or necessarily be construed as consent. Harassment is about the perpetrator’s conduct, not the victim’s response to it.

The Onus on Judges to Uphold Professional Standards

The power imbalance in this case is particularly egregious due to Mbenenge’s position.�

As Judge President, he wields immense authority, not just over his professional subordinates but also within the legal system itself.�

When someone in such a position of power crosses boundaries, it not only breaches ethical standards but also undermines public trust in the judiciary. If the judiciary cannot hold its own members to the highest standards, how can it be expected to enforce the law impartially and justly?

Legal Precedents and the Impact on Mbenenge’s Career

If Mbenenge is found guilty of sexual harassment, it could lead to his impeachment—making him the third judge president to be removed from office following Judge Motata and Judge Hlophe.�

However, this would mark the first instance in South Africa where a judge president is impeached for sexual harassment. His behaviour, if proven, would not only be morally reprehensible but would also call into question his fitness for office. A judge with such disregard for professional boundaries is not fit to hold such a significant position.

The Legal Practice Council’s Sexual Harassment Code

The Legal Practice Council (LPC) has set a clear framework for addressing sexual harassment in the legal profession. The LPC’s Sexual Harassment Policy, issued in 2020, outlines that those in positions of power, such as Mbenenge, must adhere to strict codes of conduct.

The policy stresses that harassment is not limited to physical actions but includes any unwelcome verbal or non-verbal conduct. The burden lies on the harasser, especially those in positions of power, to refrain from any behaviour that could be construed as harassment.

The Complexities of “Willing Participation” in Harassment Cases

Mbenenge’s defence might centre on the argument that the complainant was a willing participant, a common narrative in harassment cases. However, the law is clear that consent can be undermined by coercion, fear, and an imbalance of power. South African case law supports the notion that an apparent consensual interaction under duress or fear of consequences should not be considered as voluntary.

In this case, the significant age gap—Mbenenge is 63, while the complainant, Andiswa Mengo is 37—combined with his professional power and her position as the judge’s secretary raises important questions about whether true consent was possible.

The Impact of Case Law and the Role of the Judiciary

In analysing this case, we must consider previous South African case law which illustrates how power dynamics play a central role in harassment allegations.�

The legal system has consistently found that where power imbalances exist—whether in the workplace, educational institutions, or the judiciary—those in positions of authority must exercise extreme caution.�

For judges, whose role is to uphold the law impartially, engaging in behaviour that undermines professional integrity is not just unethical but a failure to maintain the standards required of the office.

An Inquiry into Ethical Integrity: A Crucial Test for the Judiciary

The ongoing inquiry into Judge Mbenenge is more than just a personal matter; it is a test for South Africa’s judicial system.�

If the judiciary cannot hold its own members accountable, what message does this send about the integrity of the legal system as a whole?�

This case will undoubtedly shape future conversations about judicial ethics, power abuse, and the need for transformation in South Africa’s legal landscape.

Conclusion: Upholding Justice, Protecting Victims

The facts surrounding Judge Mbenenge’s case are disturbing, and it is crucial that the ongoing inquiry be transparent and thorough.�

While some may focus on the complainant’s interactions with Mbenenge, it is vital to understand that harassment is not about mutual consent in such a power-imbalance situation.�

For victims of workplace harassment, particularly in hierarchical systems, the onus lies on those in positions of power, such as Mbenenge, to act ethically and responsibly.�

The legal community must continue to address the realities of power abuse and ensure that the judiciary remains a beacon of integrity.

HAVE YOU BEEN FOLLOWING THE TRIBUNAL HEARING INTO MBENENGE ALLEGATIONS?

Let us know by clicking on the comment tab below this article or by emailing info@thesouthafrican.com or sending a WhatsApp to 060 011 021 1. You can also follow @TheSAnews on X and The South African on Facebook for the latest news.