Mining is now officially in recession after two quarters of declining output. The minister’s answer to this is more ministerial control …

After two quarters of declining production, mining is now officially in recession. The once mining-heavy JSE now hosts just 35 mining companies, seven of which have no operations at all in South Africa.

In 1987, there were more than 600 listings on the JSE, with mining accounting for more than half of them. This was the engine that powered the industrialisation of SA.

Mining houses such as Anglo American and AngloGold Ashanti have fled SA, body and soul. Some such as Lonmin quietly exited, and nearly all have diversified abroad.

Glencore is suspending operations at two plants in the Glencore-Merafe Chrome Venture, citing high electricity prices, logistics challenges with Transnet rail and ports, and a downturn in the global ferrochrome market.

This comes at a cost of billions of rands in export earnings and highlights the potential difficulties of promoting minerals beneficiation when electricity prices have shot up 700% in the last decade.

ALSO READ: Mining fails to deliver jobs to local communities

How far have we slipped?

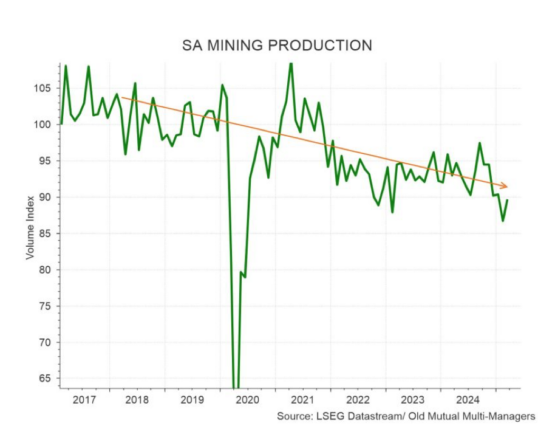

South African mining production today is 10% below where it was a decade ago and 20% lower than 20 years ago, notes Izak Odendaal, chief investment strategist at Old Mutual Multi-Managers.

This is reflected in the chart below.

Part of this can be pinned on declining commodity prices, but the longer-term trend points to something deeper and more troubling: a regulatory regime hostile to investment.

“The truth is that SA mining is uninvestible,” says Paul Miller, CEO of AramanthCX.

“Since the early 2000s we’ve had multiple mining charters, and people comb over the details, but that’s irrelevant.

“The trajectory remains the same – mining companies will be called on to give up more and more of their financial returns over time – and that will not change. This is what makes it uninvestible.”

Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe has said he wants SA to regain the 5% global exploration budgets we enjoyed in the early 2000s, but perhaps he should aim first for only 1%.

In 2024, SA claimed just 0.8% of global exploration spending, compared to Australia’s 15.9% and Canada’s 19.8%.

Any recovery in mining investment starts with exploration, which typically has a 10- to 15-year lead time before generating cash. Exploration is high risk, with no guarantee of a return.

Exploration companies have complained that besides the business risks, they are also required to take BEE partners on board.

This graph from S&P Capital IQ shows the steady de-ranking of SA mining exploration in global terms:

ALSO READ: SA opened 159 new mines in five years, creating over 15 000 jobs

Think bigger, think billions

The Industrial Development Corporation and the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy announced a R400 million fund to support exploration by junior miners, but what’s needed is more than R10 billion if we are to get back to 5% of global exploration.

We’re nowhere near that.

Mantashe’s latest attempt to ‘fix’ the mining sector is the Draft Mineral Resources Development Bill, which was released last month for public comment, with the purported aim of enhancing regulatory certainty, streamlining processes, and boosting investor confidence.

It has been met with predictable outrage and will likely achieve none of these goals.

It recycles tired and failed transformation policies.

For a start, it reintroduces the requirement for ministerial consent for any change to the shareholding of mining companies, including foreign-listed ones.

It’s hard to imagine any foreign mining company putting SA on its priority list when the minister gets to decide on shareholder changes.

Section 11 of the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA) deals with changes in ownership.

ALSO READ: Mining production disappoints again

Ministerial approval looms large

The vague language of the draft bill provides little clarity on whether an Australian miner with SA interests is required to seek ministerial approval for changes in the group shareholding, which in turn would impact the ownership of the local subsidiary.

This was decided in favour of the minister in the Supreme Court of Appeal in 2023 when it was ruled that any change in control, direct or indirect, requires ministerial consent.

“The change, if implemented, would prevent pledges of shares, the introduction of preference shares and any change in shareholding at all for a non-listed mining company without ministerial consent,” says Bowmans Attorneys.

Perhaps the biggest objection to the draft bill is that it mandates BEE for prospecting and mining rights, when all prior indications were that this would be omitted.

“The draft bill is not altogether optimal. We did have engagements with the department, but we cannot see where our inputs were taken into consideration,” says Mzila Mthenjane, CEO of Minerals Council SA.

The draft bill then introduces a new beneficiation section to the MPRDA, requiring every producer to make minerals or mineral products available for local beneficiation.

This means mining companies must offer a portion of their output for processing in SA rather than exporting raw minerals.

The bill grants the minister expanded rights to set terms and conditions for beneficiation, including oversight of beneficiation processes and approval of beneficiation plans.

Given the department’s notorious bureaucratic somnolence, it’s hard to imagine this setting the mining sector alight with enthusiasm.

Beneficiation is energy-intensive, and little thought seems to have been given to the realities of forcing miners to add value locally when electricity prices have screamed up 700% in the last decade.

No draft regulations were released with the bill, so the industry can’t assess the full impact.

Another change introduced in the bill allows the minister to designate certain areas for small-scale and artisanal mining by blacks.

This would have to be approached carefully, says Bowmans, to avoid fronting and irregular practices at both the departmental and community level.

ALSO READ: ‘If they don’t give us money, let’s not give them minerals’: Mantashe hits back at Trump funding cut

Industry trying to stay afloat

Is there a way to turn this ship around? Odendaal says there is.

Increased mining production and exports require the following, among other things:

- Capital for exploration, feasibility, and construction;

- A conducive and predictable regulatory regime;

- A working public repository of mining rights and geological information (cadastre) – this is finally and belatedly being implemented;

- Stable labour relations;

- Safety and security;

- Community buy-in – unlike other businesses, mines cannot choose where to operate; and

- Water, energy, and logistics infrastructure – letting mining companies run their own trains would be a good start.

Adds Miller: “A new generation of reforming politicians will have to make the root and branch changes required to fix our mining sector, and it will have to be done on the wreckage of the existing system.”

This article was republished from Moneyweb. Read the original here.