Although 2024 was full of knocks and financial drama, the country’s middle class is upbeat about their finances and the future.

South Africa’s middle class had a hard year and you have to wonder how they feel heading into December when they get time off, maybe a little bonus in the bank and time to rethink and regroup ahead of 2025.

It has been a tough year filled with water shortages, elections and global crises and the big question for retailers and brands must surely be whether there is light at the end of the tunnel.

A major factor in answering that question is knowing exactly what is going on in the hearts, minds and bank balances of consumers, Brandon de Kock, director of storytelling at BrandMapp, says.

“Right now, in the media, there is a cacophony of alarm bells ringing out over rising debt, cost of living crises and the financial constraints that the South African middle-class face. Income growth, the story goes, is outpaced by significant cost increases and consumers must resort to credit and loans to make up the shortfall.

“And there is also chatter in the media that the major banks are recording an increase in the numbers of their clients who are living pay-cheque-to-pay-cheque.”

ALSO READ: Consumer confidence slips in fourth quarter, but still better than last year

Not everyone in the middle class is pessimistic about finances

However, De Kock says, all this does not necessarily mean that most of the country’s formally employed income earners are feeling pessimistic over finances. “Our research, which measures what is going on in the lives of the 13 million South African adults living in taxpayer households, gives us the deepest, widest view of this critical segment that anyone’s ever seen.

“What is clear is that a true understanding of where things are at requires you to separate the baby from the bathwater, so to speak.”

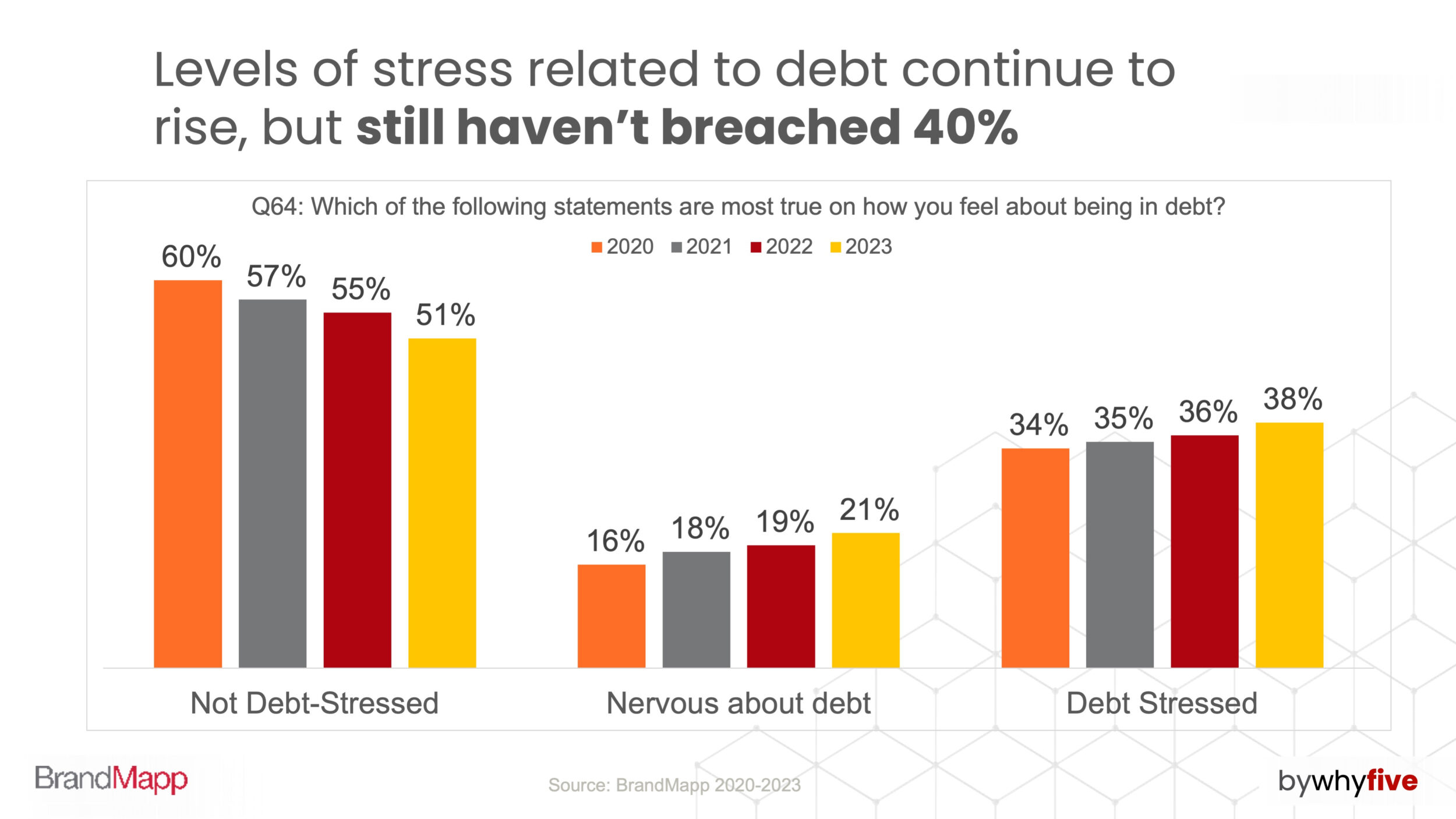

He says consider, for example, the levels of debt stress these consumers expressed over the past four years. “The percentage of people saying they have no debts at all or are not at all worried, has shrunk from 60% to 51% in the past four years, with the biggest jump coming in 2023.

“However, the story is not all bleak. When you look at the BrandMapp audience, fewer than 30% are actually ‘debt-stressed’ and that number drops to just 13% for households earning R1 million or more per year. More importantly, a massive 51% of all consumer-class adults are either debt-free or not at all concerned about their debt.”

ALSO READ: Many wealthy taxpayers are leaving SA due to increasingly high taxes

Age dynamics are also important in how middle class feels

De Kock points out that age dynamics also play a significant role. Gen Z and Boomers stand out as the least debt-stressed, with about 45% having no debt at all, while 35-55-year-olds bear the brunt of debt stress, with 35% in this cohort feeling burdened by its weight.

“The reality is that more highly educated, employed adults know how to deal with debt and use it as a tool to achieve their preferred lifestyle rather than a necessity. Yes, there are certainly new-to-category consumers borrowing themselves into a lifestyle, but the data indicates that they are in a minority, not the majority.”

What then keeps South Africa’s mid-to-top earners awake at night? De Kock says financial concerns loom large, but they are not the sole worry for South Africa’s middle class.

“BrandMapp 2023 shows that 47% of adults say that the thought of ‘rising food and energy costs’ keeps them awake at night. Other significant stressors include weak economic growth for 40% of the BrandMapp audience. But they are still more concerned with crime and corruption than either of those.”

ALSO READ: The difference between a R15 000 living wage and the minimum wage

Resilience shines through despite challenges

But despite these challenges, resilience shines through. De Kock points out that almost 60% say they are the same, or better off than they were two years ago, with only 15% saying they are ‘much worse off.’

“Encouragingly, South Africa’s high-income earners are growing at twice the rate of inflation, while the millionaire class of people earning R1 million or more per year is expanding at a staggering rate of 20% or more.”

De Kock points out that this is not just about the rich getting richer. “There is a rapidly growing economic elite forming at the top of the country’s income pyramid. It means that the tax burden on the super-wealthy is actually getting better and not worse.

“This also means that if we can turn things around on a macroeconomic level, there is a highly skilled, educated and motivated group ready to pull the country into a brighter future.”

ALSO READ: Repo rate cut too little too late for consumers on edge of financial ruin?

Shifts in the middle class’s spending behaviour and attitude toward wealth

He says BrandMapp also noticed shifts in spending behaviours. “Financial constraints are reshaping spending patterns but not uniformly. At the middle and bottom of the income pyramid, consumers are driven by survival and do not really have much choice.

“But the higher up the tree you go, the more choice consumers have. This indicates that discretionary spending, such as dining out or buying new cars, is postponed rather than abandoned.”

Interestingly, aspirations remain steady, with 37% of adults wanting to buy or change their cars this year, while 22% are looking to buy a house, only a slight drop from 28% three years ago.

“Affordability is obviously an issue, but I think this also reflects increasing numbers of incoming-earning younger adults, the ‘subscription generation,’ who see things like home loans as anchors tying them down rather than steps up the ladder.

“And they also live in a new consumer world with all kinds of novel behaviour influences and therefore there is a growing trend toward ‘staying at home more,’ fuelled by streaming services and home delivery options that continue to radically transform consumer behaviour.”

There has also been a change in attitudes towards wealth and resilience. Facing economic uncertainty and the soaring cost of living, South Africa’s middle class remains cautious and measured in their approach to wealth-building.

When asked about how they describe their attitude towards investments, only 28% of the BrandMapp audience say they are ‘bold’, while 41% are ‘conservative’ and the rest are unsure.

“This conservatism indicates a ‘treading water’ sentiment, particularly among higher-income groups who can afford to play the long game,” De Kock says.

ALSO READ: Can lower fuel price and repo rate help South Africans save?

A tale of two economies?

Is it a tale of two economies? “South Africa’s financial landscape reveals stark contrasts. What we are seeing is the ongoing expansion of a stratified society and we must be extremely concerned about the plight of the ever-expanding number of individuals who sit in the 70% of adults in the country and live in a world of very limited choice below the tax-paying threshold.

“But, at the same time, we should not lose sight of the fact that the group of consumers who do have choice is growing at exactly the same pace and the group at the very top is growing faster than anything else.

“It is not a tiny elite, it is now somewhere around five or six million adults who live in a country within a country, one full of dreams that can actually be reached. It is a story about evolution, not revolution and it is one that we have specialised in ununderstanding for the past 11 years.

“I cannot wait to see what the new BrandMapp data will show us. But if you take rising levels of consumer optimism into account, I really believe it is going to be another chapter with a happy ending.”