‘South Africa is seeing a sharp increase in issues with access to nutrition leading to greater food insecurity.’

Food security in South Africa is at its lowest point in a decade, while child hunger remains a major issue, according to a new food security index.

In addition, the South African Food Security Index 2024 shows that 11.8% of households said they were eating a lower variety of food than usual due to economic constraints. At a national level, food availability declined from a peak of 2.8 tons of raw food per person per year in 2017 to 2.6 tons in 2022.

The index also shows that households headed by men have lower risks of hunger (12.5% in rural areas and 8.7% in urban areas) than those headed by women (16.7% in rural areas and 11.9% in urban areas).

The index was published on Wednesday on World Food Day and contains some shocking statistics. It was compiled by prof Dieter von Fintel, vice dean for research, internationalisation and postgraduate affairs in the faculty of economic and management sciences at Stellenbosch University and Dr Anja Smith, a development economist and part-time researcher at the Research on Socio-Economic Policy (ReSEP) unit at Stellenbosch University’s economics department.

Shoprite commissioned the index to enable a deeper understanding of the state of food security, highlight where some of the biggest gaps may exist and help inform better decision-making.

ALSO READ: ‘Many households are food insecure’: Survey reveals ‘grim picture’ for ordinary, poor South Africans

What is food security?

The concept of food security was first defined at the 1996 World Food Summit as a situation “where all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for a healthy life.”

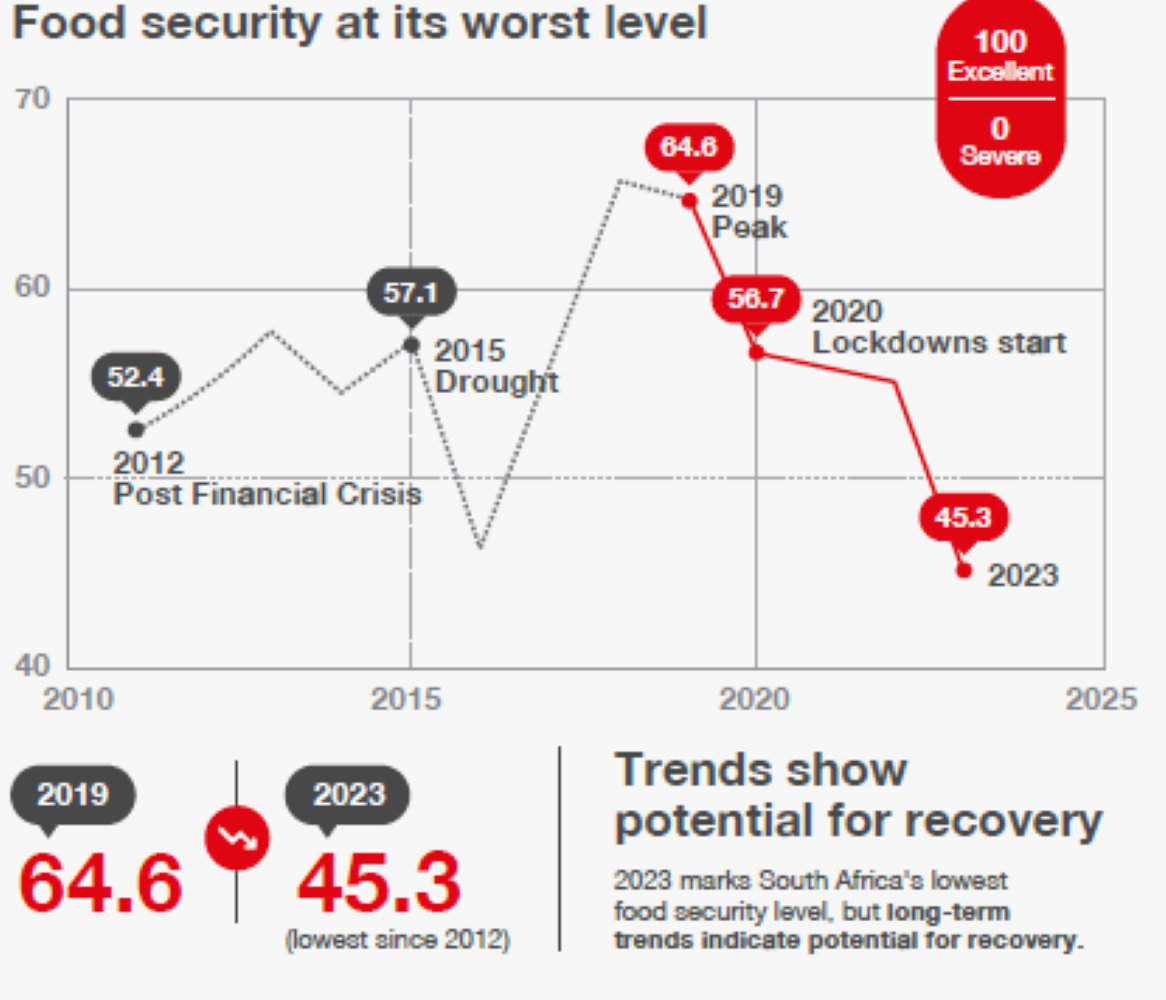

South Africa peaked at 64.9 on the Index in 2019, but this number dropped to 45.3 in 2023 (zero indicates severe food insecurity). This means that more South Africans on average experienced greater food insecurity in 2023 compared to any other year since 2012.

The Index evaluates four dimensions of food security, namely availability, access, utilisation and overall stability from 2012 to 2023 and creates a baseline to measure food security in South Africa yearly using publicly available and annually updated data.

ALSO READ: Half of SA population will be food insecure by 2025

Availability of food as part of food security

Regarding the availability of food, Von Fintel and Smith say it remains a struggle for people, with many having very limited diets. Availability is affected by how much food is produced in the country, impacted by socioeconomic and political conditions but also by environmental factors.

The number of people in South Africa not meeting the minimum energy requirements (1,834kcal) increased from 1.8 million in 2001 to 4.7 million in 2021.

When it comes to economic and physical access to food, von Fintel and Smith point out that although a country may have a sufficient supply of food, households may not have adequate access to food due to economic and physical reasons.

ALSO READ: Various areas in KZN experience food insecurity, here are the solutions

Access to food

“Access to food is a basic human right, but South Africa is seeing a sharp increase in issues with access to nutrition leading to greater food insecurity. Access is often misunderstood – the access to food is the ability of a person to eat a balanced, high quality and diverse diet. The location of stores, or the availability of items in store has an impact on the access dimension.”

They say while availability has remained stable, access to food has improved. In 2002 one quarter of all households experienced some form of child hunger. By 2023 one quarter, or one in four, of the poorest households experienced child hunger, compared to only 11.8% (or one in ten) of all households.

Von Fintel and Smith also point out that hunger declined rapidly with the expansion of social grants in the early 2000s, especially the Child Support Grant. By 2007, hunger rates dipped to 12% of households, but the financial crisis briefly reversed some of this progress, as did the short period after the 2015 drought.

“While there were small dips and increases in hunger between the early 2000s and 2020, there has been an overall decrease in hunger but since the Covid-19 pandemic, hunger has increased.”

ALSO READ: Food basket price increases, core foods remain expensive

Utilisation of food as part of food security

Utilisation of food refers to how the body uses food to generate energy and help support an individual’s health. For the body to use food properly, people or families must eat a diverse diet where food is well prepared, ensuring maximum nutritional value.

Smith and Von Fintel say with food access (hunger), there has been an increase in the proportion of households reporting low food variety since 2019. By 2023, 23.6% of households said they were eating a lower variety of food than usual due to economic constraints.

They emphasise that there may be periodic dips or deterioration in the availability, access and variety when it comes to food due to factors that include weather conditions (floods or droughts), economic factors (food inflation and stable employment) and political instability, like war.

ALSO READ: Expert says child grant must be increased

The dire consequence of food insecurity – stunting

The consequences are dire. The researchers say South Africa has a nutrition problem which is showing up in stunting, a measure of impaired growth. Children are stunted when they do not reach their full growth in terms of height relative to age.

“Children who are stunted achieve lower levels of cognitive outcomes, in turn going on to have lower later-life labour market earning potential. While stunting can have many causes, it often occurs when young children do not get the nutrients required to sustain proper growth.”

Von Fintel and Smith point out that although stunting is expected to decline with the level of a country’s wealth and South Africa is regarded as an upper-middle income country, our stunting rate is high.

“South Africa is one of 34 countries accounting for 90% of the world’s stunted children putting us in the same group as some of the poorest countries in the world, such as Mozambique, Afghanistan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

ALSO READ: Households worry about food running out before month-end

Stunting in SA compared to Brazil and Zimbabwe

“Brazil, like South Africa, is an upper-middle-income country with similarly high levels of inequality. With a similar gross domestic product (GDP) per person, Brazil had a stunting rate of 7% in 2007, while South Africa had a stunting rate of 21.4%. Other data sources put our stunting rates around 24.0% in 2019.

“Zimbabwe is classified as a lower-middle income country and has faced many economic crises. In 2019, Zimbabwe was a significantly poorer country than South Africa but had a similar stunting rate of 23.5%.”

Von Fintel and Smith say better nutrition in children leads to the avoidance of stunting while ensuring they receive enough kcals to learn in school. They warn that although South Africa has been able to improve food insecurity in the past, the Index indicates that the situation could worsen over the next decade if immediate interventions are not implemented with speed.

ALSO READ: World Food Day: SA Harvest’s Alan Browde calls for action to prioritise nutritious food

Steps required to improve food security

They recommend these concrete steps to reduce food insecurity:

- Ensuring children regularly eat more affordable and accessible foods to help avoid stunting include chicken livers, tinned fish such as sardines, eggs, chicken, peanut butter, milk, maas, plain unsweetened yoghurt, dark green leafy vegetables such as spinach or indigenous green leaves and yellow, orange and deep red vegetables and fruit, such as carrots, tomatoes, pumpkin, orange-flesh sweet potato, apricots, or mangoes.

- National Treasury must strongly consider zero-rating VAT on certain key food products, especially protein-rich items used by lower-income households that include affordable protein sources.

- Substantial support for households to establish food gardens with nutritious vegetables and fruit.

- Prioritising nutrition interventions during the first 1,000 days of children’s lives, with nutritional support for young children, to prevent stunting. This should include providing protein-rich food at early childhood development centres, as well as at early learning programmes.

“One of the most concerning observations in the Index is that child hunger remains a major issue. As many as one in four children are growth stunted – a number which is especially alarming given the country’s overall level of economic development,” Sanjeev Raghubir, chief sustainability officer for the Shoprite Group, says.