A lower inflation target will ensure lower inflation which will, in turn, ensure lower interest rates at no cost to the economy.

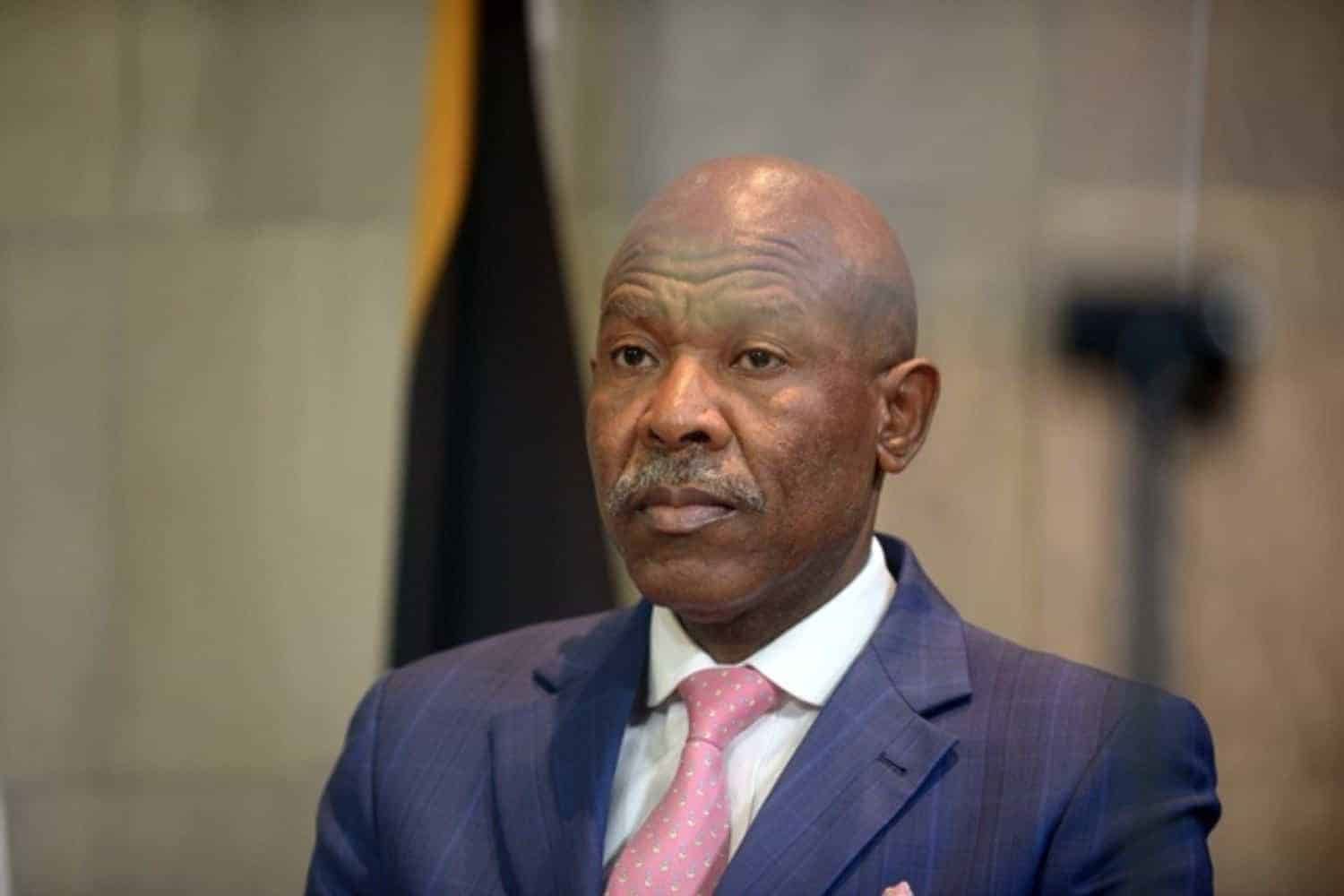

Reserve Bank governor, Lesetja Kganyago, would like South Africa’s inflation target to be lower than the current target band of 3% to 6%, as the country was able to lower inflation to 4.5% without too much pain or cost.

Kganyago was a guest lecturer at the department of economics at Stellenbosch University last week and spoke about the lessons the South African Reserve Bank (Sarb) learned moving inflation to 4.5% and what it cost to do that.

He said the first lesson from the global inflation surge is that people really hate inflation. “Many economists were surprised by the depths of public unhappiness with high inflation. This has been especially clear in advanced economies that had very low inflation over a sustained period, usually 2% or less.

“At those rates, most people did not have to worry about it. But after the Covid-19 pandemic, they suddenly experienced the kind of price increases usually found in poorer countries and they hated it even more than expected.”

ALSO READ: South Africa’s inflation outlook improving but risks remain

Monetary policy worked

Kganyago said the second lesson was about the effectiveness of monetary policy and what works and what does not. “Something that did not work was the ‘transitory’ argument, the claim made in 2021 that high inflation would be temporary and there was no need for a monetary policy response.”

He pointed at another failed claim in 2022: that inflation would come down only through a severe recession, with a big increase in unemployment. However, inflation in major economies, like the US, fell from about 9% to just over 2%, with no recession and steady job growth.

“Looking at this record, you could say that central bankers either got it right or they got lucky. My sense is that they made their own luck.”

There is no question that supply-side factors helped, he said. “We had lower oil price inflation, lower food price inflation and better supply-chain functioning after the Covid-19 disruptions. But it is equally clear that the monetary policy response is part of the story.”

Kganyago pointed out that forceful policy responses put the brakes on inflation and also helped to convince the public that central banks were committed to low inflation and that high inflation was an aberration, not the new normal.

ALSO READ: Inflation now expected to average 5.1% this year

Lower inflation does not need recession and high unemployment

“The lessons are that it was wrong to say we could have low inflation for free, that we could just look through shocks, keep rates low and all would be fine. But it was also wrong to say that lowering inflation would require a recession and large-scale job losses: a soft landing was an attainable goal.

“What we have seen is a reminder that good monetary policy can deliver low inflation at a modest cost. It does that by safeguarding the low inflation regime, which has its own self-stabilising properties. Given how strongly people dislike inflation, this is clearly the space we want to occupy.”

Turning to South Africa’s inflation experience, Kganyago said the country implemented inflation targeting nearly a quarter of a century ago in 2000. “Looking back, the framework has been generally successful. Both inflation and interest rates have been lower than they were before inflation targeting.

“Inflation has also been within the 3−6% target range, on average. However, this average has been on the high side of the target range. Since 2000, using the ‘targeted inflation’ measure, it has averaged 5.85%.”

He acknowledged that the country missed the target quite often, almost exclusively to the upside. “We have been above the 6% upper bound of the target nearly 40% of the time, compared to only 1% of outcomes below the 3% lower bound.”

ALSO READ: Inflation dips below 5% in July for the first time in 3 years

Sarb’s shortcomings with inflation targeting

When the Sarb reflected on its record soon after Kganyago was appointed governor, it identified three shortcomings:

- The Sarb was missing its target too frequently although 3−6% is one of the wider targets around and therefore should have been relatively easy to hit most of the time

- The average inflation rate was high, mostly near 6%. This did not amount to a crisis and it was much better than the double-digit rates seen in the 1980s and 1990s. But at 6% inflation, prices double in just over a decade and triple in two decades.

- The Sarb realised that the economy had a structural growth problem. After the global financial crisis, South Africa’s growth slowdown was diagnosed as a weak demand problem. To deal with it, the Sarb tolerated higher inflation so that it could avoid rate increases and restore growth. It did not work as growth never came back and we just ended up with high inflation.

“Accommodative monetary policy was the wrong medicine for the patient. These hard truths prompted us to try a new strategy.”

ALSO READ: Inflation outlook improved in recent months – good news for repo rate cut

Changing aim to the middle of 4.5%

In 2017, the Sarb began emphasising that it wanted inflation in the middle of its target range, at 4.5%.

“We would not treat 3−6% as a ‘zone of indifference’, which in practice meant aiming for the top of the range and ignoring the bottom half.

“Rather, we were explicit that we wanted to be at the midpoint, over time. The range would be there to handle volatility, which is inevitable with inflation. But over time, the Sarb would always be working to bring inflation back to 4.5%.”

He said we often speak as if high inflation is a structural, inevitable thing and not a policy choice. “But the fact is, we could have a lower inflation target, like almost all our peers and with it lower inflation.

“If we achieved this, I think South Africans would enjoy the lower inflation experience and will look back at the era of inflation generally over 5% as a period of great inconvenience and difficulty. People prefer price stability. We cannot honestly claim that we are delivering that. We can do better.”

Kganyago also emphasised that in discussing inflation in South Africa analysts too often misrepresent the administered price problem. “Yes, administered price inflation is too high and damaging for the economy. Yes, if it were lower, that would help deliver lower inflation and lower interest rates.

“But administered prices are also responsive to economy-wide inflation and they are not such a large part of the basket that disinflation can only be achieved by forcing everyone else into deflation. The conversation about lower inflation should not be held hostage by administered prices.”

ALSO READ: Food inflation lowest in 45 months

Lower inflation does not mean lower growth

In addition, he pointed out that it is still often assumed that lower inflation means lower growth, despite rigorous studies showing that sacrifice ratios can be low. “It is depressing enough that short-term pain is considered such a decisive argument against long-term gain.

“But it is even worse that it is considered a winning argument when it is not even clear there is short-term pain. The studies of the move to 4.5% inflation certainly do not show high costs. They show a path to lower inflation that relies mainly on communication and credibility, rather than high rates.”

Kganyago said these misconceptions leave us with a macroeconomic discussion that is too pessimistic and insufficiently ambitious.

“We have an opportunity to achieve permanently lower inflation and therefore permanently lower interest rates. Executed effectively, a lower target could be achieved at little cost – just as we moved to 4.5% at little cost.”